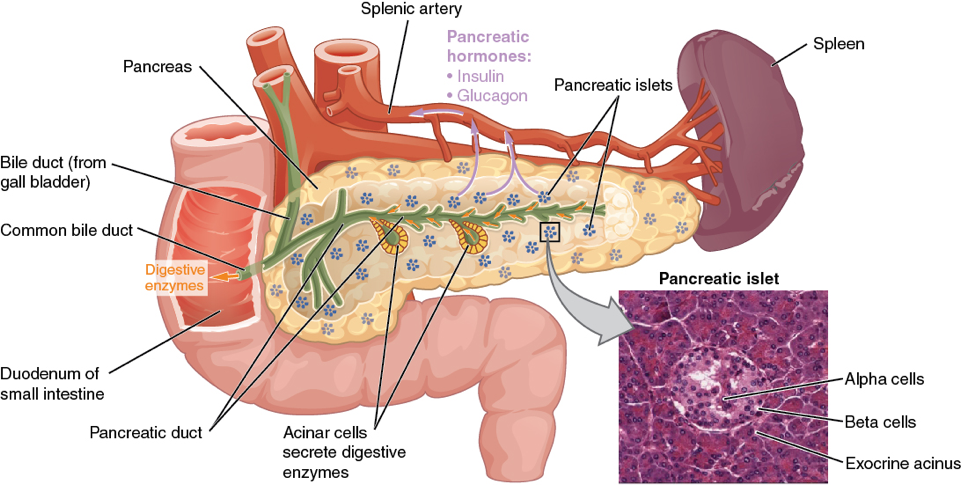

Diabetes mellitus is often described as “starving in the land of plenty” meaning that every cell in the body, and in particular the central nervous system, needs sugar, the gasoline or fuel of the body, to function properly. However, in order for this “fuel” (sugar) to properly enter the body it requires a hormone called insulin that is produced by thousands of tiny little islands of cells (islets of langerhans) laced throughout the pancreatic organ.

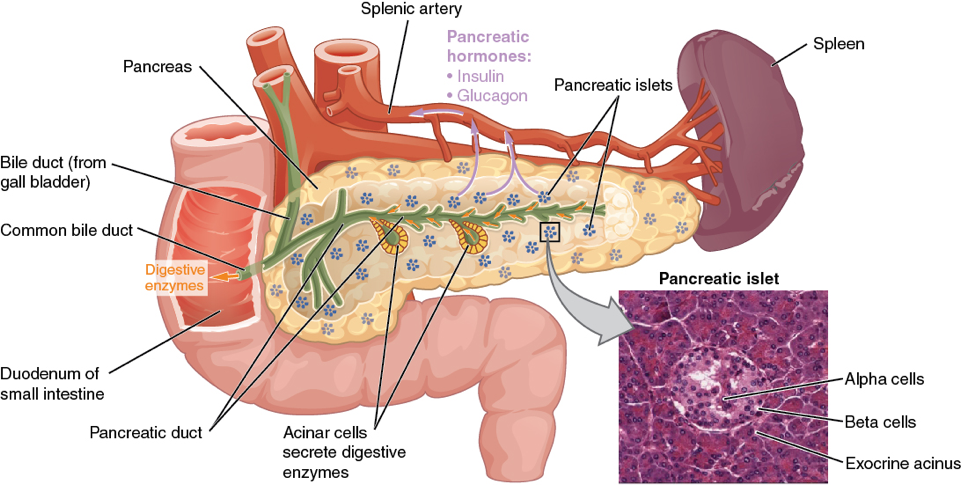

The pancreas has two major and diverse functions:

The exocrine portion makes up the majority of the pancreas and produces the potent digestive enzymes that breaks down food into smaller particles for absorption and fuel; and the other major function, in lesser amounts, is the endocrine portion that synthesizes and releases several hormones into the bloodstream with insulin being the most important of these.

Pancreas

(Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

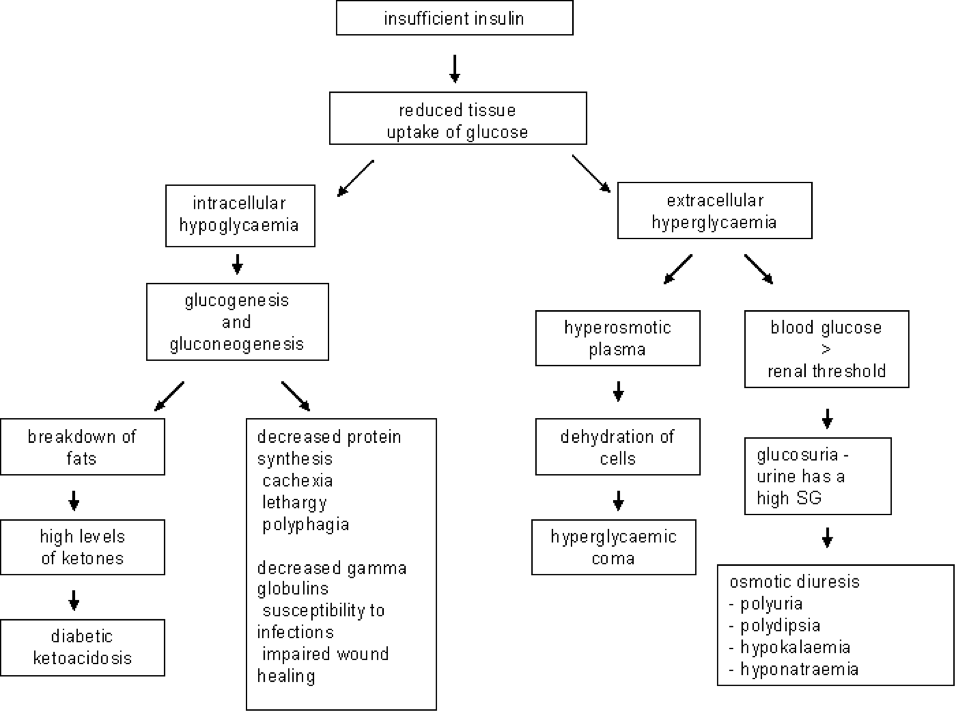

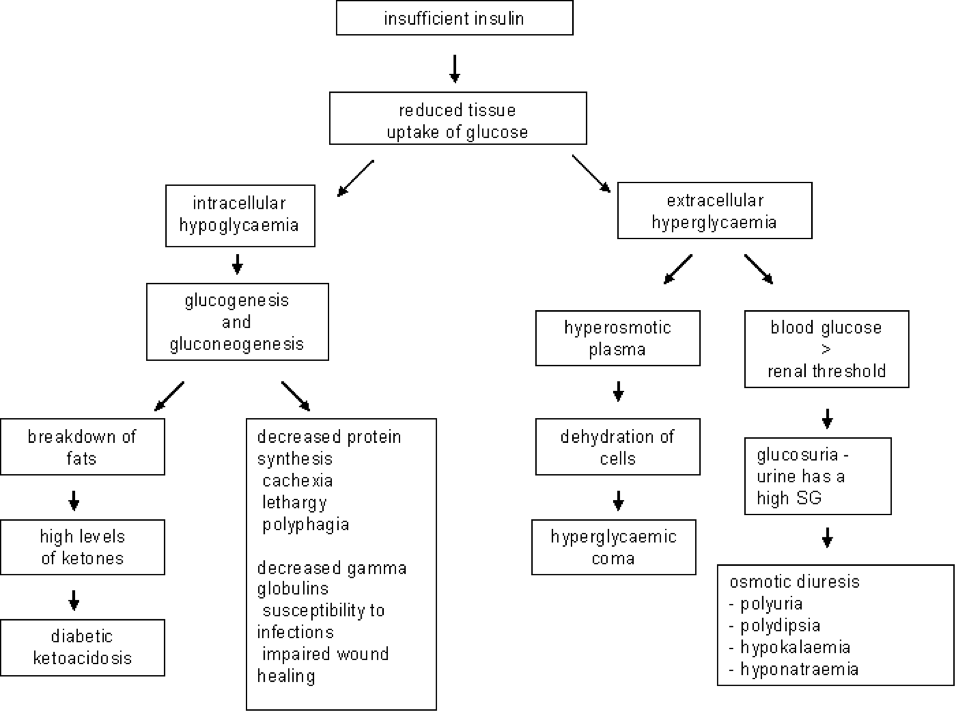

When the pancreas fails to produce enough insulin; the body is in a state of crying for help:

“give me energy, give me sugar, give me fuel to function”, but with suboptimal levels of insulin available the glucose (sugar) cannot effectively move from the bloodstream into the body cell.

In essence, the body is literally “starving to death in the land of plenty” meaning there is plenty of available glucose (fuel) in the bloodstream, but without insulin it’s just not getting to where it is needed the most; which is every cell in the body.

This leads to a number of negative metabolic abnormalities with the most common signs being an increase in thirst and urinations; panting; diminished to no appetite; vomiting, weight loss and generalized malaise. The “net effect”, when insulin is unavailable, is the body is in desperate need for fuel and starts to break down its own body fats as a poorer source of utilizable fuel. Eventually, this leads to an overwhelming increase in body acids (ketoacidosis) which leads to even more serious signs of dehydration, loss of appetite, malaise, vomiting, sepsis, coma and eventual death.

Pathophysiology of Diabetes Mellitus

The Main Clinical Signs of Diabetes Mellitus are:

- Increased thirst

- Increased urination

- Voracious appetite initially and diminished when the condition worsens

- Weight loss due to fat breakdown and loss of appetite

- Urinary tract infections are a common finding

- Cataracts

- Vomiting, panting, dull, coma, and death

Classification of Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is classified as either Type I or Type II as well as other subcategories.

Type I form of diabetes, also referred to as “insulin dependent diabetes”, is defined as an “absolute lack of” or “suboptimal amounts of” insulin production. Animals with Type I diabetes require insulin by injection for survival … for life.

This is by far the most common form of diabetes we see in the dog with the most common underlying cause being inflammation and destruction of the pancreatic islet cells due to pancreatitis; autoimmune disease; drugs; etc..

Type II form of diabetes, also referred as “non-insulin dependent diabetes” occurs due to one of several possibilities:

Obesity is by far the most common cause of Type II diabetes in humans and animals. Acromegaly (excessive growth hormone), Cushing’s syndrome (excessive cortisone) and various drugs are common contributing factors that lead to an increased demand by the body for higher than normal amounts of insulin (insulin resistance). This is the body’s attempt to maintain a normal blood sugar, in the face of these various insulin resistant factors, by producing higher amounts of insulin to overcome these resistances. With time, this constant demand for more insulin results in islet cell exhaustion, low insulin production, high blood sugar and full blown diabetes in both the dog and cat.

However, the most common finding, peculiar to cats with diabetes, is the finding of a non-dissolvable and non-treatable substance, called amyloid, that deposits within these insulin producing islet cells. This amyloid deposition results in a slow, but progressive, destruction of the insulin producing islet cells. The remaining viable islet cells still have the capability of producing insulin, but often in suboptimal amounts and not enough to keep up with the normal feline metabolic requirements. These cats will often require insulin management initially, but many can be weaned off insulin injections and regulated with dietary manipulations, weight reduction, and oral hypoglycemic drugs. However, the vast majority of these animals will eventually require insulin injections as their Type II diabetes, with further islet destruction by amyloid, progresses to Type I diabetes and they become insulin dependent.

Paul G. Cavanagh, DVM, DACVIM (SAIM)

Future Articles by Dr. Cavs:

Insulin & Oral Hypoglycemics; Diabetic Testing: what do they mean and why do we need them?; Diet in Diabetics: The Carnivore Connection;

Zika Virus and Animals

March 7, 2016 (published)

J.Scott Weese, DVM. DACVIM

I’ve been getting a lot of questions about Zika virus and animals. It’s great lo see that people are thinking more broadly about infectious diseases (but it isn’t doing much for my productivity this week).

To recap, Zika virus is a mosquito-borne virus related lo West Nile virus and dengue virus. Most people that are infected don’t get sick at all, and when they do, they usually get only mild signs of illness that resolve on their own. In the past few years, Zika virus has emerged in the Americas, particularly Brazil. Very recently, a link (still unproven) between infection of pregnant women and birth defects (babies born with small heads and brains [microcephaly]) has been reported, predominantly in Brazil.

Anti mosquito sign ,flat icon, vector

Can animals get infected with Zika virus?

- It depends on what you include in “animals.” We could be technical and say that humans are animals.

- Beyond that. non-human primates are susceptible. Zika was first identified in 1947 when

yellow fever researchers working in the Zika forest in Uganda stumbled onto it. They had a macaque in a cage and it developed a febrile illness from something that was transmissible. The virus was described as Zika virus in 1952 and then found in people a couple of years later.

But can domestic animals gel infected with Zika virus?

- Again, we need to think about the question. Infected means they get exposed lo the virus and it replicates in the body. That may occur, but we don’t have any evidence of it at this point.

- The more relevant question is whether animals can get sick from Zika virus exposure, and there’s also no evidence of that to date.

- A third aspect is whether infected (but potentially healthy) animals could be a reservoir for the virus, being able to pass it on to mosquitoes. There’s no evidence of that. either.

So, the clearest answer is probably “maybe.” When it was a flu-like illness confined to some regions in Africa, Zika wasn’t a high priority so research hasn’t been extensive. The risk to pets in areas where the virus is circulating (areas where there are Aedes egpyti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes) is probably very low. It would be good to look into the risks associated with domestic animals, including their susceptibility to disease and potential roles as reservoirs, but the likelihood that there is a relevant issue with either of these is probably remote.

So, the clearest answer is probably “maybe.” When it was a flu-like illness confined to some regions in Africa, Zika wasn’t a high priority so research hasn’t been extensive. The risk to pets in areas where the virus is circulating (areas where there are Aedes egpyti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes) is probably very low. It would be good to look into the risks associated with domestic animals, including their susceptibility to disease and potential roles as reservoirs, but the likelihood that there is a relevant issue with either of these is probably remote.

Protecting your cat or dog (or both) from ticks is an important part of disease prevention. In fact, there are several diseases that can be transmitted to your pet from a tick bite. The four most common tick-borne diseases seen in the United States are Lyme disease, Anaplasma, Ehrlichia and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. Here we will briefly discuss these tick-borne diseases that affect both dogs and cats.

Lyme Disease

Also called borreliosis, Lyme disease is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi. Deer ticks carry these bacteria, transmitting them to the animal while sucking its blood. The tick must be attached to the dog (or cat) for about 48 hours in order to transmit the bacteria to the animal’s bloodstream. If the tick is removed before this, transmission will usually not occur.

Common signs of Lyme disease include lameness, fever, swollen lymph nodes and joints, and a reduced appetite. In severe cases, animals may develop kidney disease, heart conditions, or nervous system disorders. Animals do not develop the tell-tale “lyme disease rash” that is commonly seen in humans with Lyme disease.

Blood tests are necessary to diagnose Lyme disease in pets. If the results are positive, oral antibiotics are given as treatment for the condition. Dogs that have already had Lyme disease are able to get the disease again — they are not immunized against it — so prevention is key. A vaccine for Lyme disease is available for dogs, but unfortunately, the vaccine is not available for cats. If you live in an area where these ticks are endemic, you should have your dogs vaccinated yearly.

Anaplasmosis

Deer ticks and western black-legged ticks carry the bacteria that transmit canine anaplasmosis. Another form of anaplasmosis (caused by a different bacteria) is carried by the brown dog tick. Both dogs and cats are at risk for this condition. Because the deer tick also carries other diseases, some animals may be at risk for developing more than one tick-borne disease at a time.

Signs of anaplasmosis are similar to ehrlichiosis and include pain in the joints, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, and possible nervous system disorders. Pets will usually begin to show signs of disease within a couple weeks after infection. Diagnosis of anaplasmosis will usually require blood tests, urine tests, and sometimes other specialized lab tests.

Oral antibiotics are given for up to a month for treatment of anaplasmosis, depending on the severity of the infection. When treated promptly, most pets will recover completely. Immunity is not guaranteed after a bout of anaplasmosis, so pets may be reinfected if exposed again.

Ehrlichiosis

Another tick-borne disease that affects dogs is ehrlichiosis. It is transmitted by the brown dog tick and the Lone Star Tick. This disease is caused by a rickettsial organism and has been seen in every state in the U.S., as well as worldwide. Common symptoms include depression, reduced appetite (anorexia), fever, stiff and painful joints, and bruising. Signs typically appear less than a month after a tick bite and last for about four weeks.

Special blood tests may be needed to test for antibodies to Ehrlichia. Antibiotics are usually given for up to four weeks to completely clear the organism. After infection, the animal may develop antibodies to the organism, but will not be immune to reinfection. There is no vaccine available for ehrlichiosis. Low doses of antibiotics may be recommended for animals during tick season in areas of the country that are endemic to this disease.

Tick prevention for Dogs breed Griffon Bruxellois

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

A disease seen commonly in dogs in the east, Midwest, and plains region of the U.S. is Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF). Cats can be infected with RMSF, but the incidence is much lower for them. The organisms that cause RMSF are transmitted by the American dog tick and the Rocky Mountain spotted fever tick.

The tick must be attached to the dog or cat for at least five hours in order for transmission of the organism to occur. Signs of RMSF may include fever, reduced appetite, depression, pain in the joints, lameness, vomiting, and diarrhea. Some animals may develop heart abnormalities, pneumonia, kidney failure, liver damage, or even neurological signs (e.g., seizures, stumbling).

Blood tests can show antibodies to the organism, signifying that the animal has been infected. Oral antibiotics are used for about two weeks to treat the infection. Animals that are able to clear the organism will recover and remain immune to future infection. However, if your dog or cat has heart, liver, or kidney damage, and/or the nervous system has been affected by the infection, it may require additional supportive treatment, generally in hospital.

Currently, there is no vaccine available to prevent RMSF, so tick control is very important for animals living in endemic areas.

By Jennifer Kvamme, DVM from mypetMD

Edited by Paul G. Cavanagh, DVM, DACVIM (SAIM)

People show up at animal shelters and rescue groups in New York City all the time with this problem: they think they have to get rid of their pets or they’ll be evicted.

They’re often wrong.

In New York City there’s a program called Pets for Life NYC that lets people know what their rights are and often helps them keep their pets. Calling Pets for Life (917-468-2938) can point you in the right direction.

Darryl Vernon, a New York attorney who specializes in tenants’ rights to have pets, says, “It’s crucial that people talk to a lawyer very early so they understand their rights.” For starters, there’s a three-month law that protects pet owners who live in buildings with three or more units. According to Vernon, the best thing is for people to know about the three-month rule and their rights under the disability laws. “Both are powerful defenses against any action brought by a landlord or co-op or condominium to make someone get rid of their dog or move out of their home,” he says.

According to Companion Animals in NYC Apartments – 2009 Edition, a brochure published by the NYC Bar Association Committee on Legal Issues Pertaining to Animals, “once a companion animal lives in a multiple dwelling (a building with three or more residential units) for three or more months, openly and notoriously (not hidden from the building’s owners, their agents, and on-site employees), then any no-companion animal clause in a lease is considered waived and unenforceable.”

Unfortunately, many people give up their pets because they’ve signed a lease that specifies no cats or dogs, and they think that’s it. But the three-month rule overrides any agreement to the contrary.

The law also says tenants aren’t obliged to tell the landlord or his/her building agents about their pet. If a building employee knows of the pet, even if the building owners don’t know, that starts the three-month rule running. If the landlord doesn’t bring legal action against you within that three-month period, your pet is in like Flynn. Even if your landlord tells you to get out, you don’t have to. Only a judge can order you out.

If your landlord wants you to move because your pet does things that irritate your neighbors, you can get help for that, too. Pets for Life NYC can connect you with trainers and behaviorists who will work with you and your pet to correct the bothersome behavior.

And there other recourses available to you. For example, if the “no pet” provision in your lease is in type smaller than eight points or otherwise visibly unclear, then your landlord can’t use that lease as evidence to get rid of you.

Also, disability laws override any agreement to the contrary. “It’s like writing an agreement that if you need a wheelchair, you can’t bring it into your apartment. You can’t discriminate against people who have a disability. And a reasonable accommodation can, in many instances, mean having a dog or other companion animal in your apartment,” says Vernon.

Federal, state, and city laws may also protect your right to have your companion animal. Companion Animals in NYC Apartments – 2009 Edition states: “Under the federal Fair Housing Act 22, people with disabilities have been successful in arguing that, in certain circumstances, landlords must allow them to have a companion animal who provides them with emotional support as a reasonable accommodation.”

According to Vernon, any animal can be a service animal. He explains, “What defines a disability? The exact words are ‘your disability substantially interferes with a major life activity.’ That can be a whole host of things, like high blood pressure that’s so bad it interferes with major life activities, meaning work, socializing, eating, or going out. And depression is a disability. Not just everyday depression, but something chronic, serious, very debilitating. Depression can easily interfere with major life activities.”

But don’t take your animal in to be certified, take yourself. You’ll need to get a letter from your health care provider, the details of which are illustrated in this sample letter. When your companion animal has been determined to be “medically necessary,” a court can rule that your pet must be permitted to live with you.

Westchester County has similar laws. The ASPCA and The Humane Society of the United States are working with other states to develop similar programs. Anita Kelso Edson, Senior Director of Media and Communication for the ASPCA, says “The emotional support animal concept is rooted in federal law, so it would be the same state to state.”

In New York City, the only animals that aren’t protected by the pet law are those whose owners live in New York City Housing (NYCHA). The New York City Housing Authority last year passed a law prohibiting any dog weighing over 25 pounds or any Doberman, Pit Bull, or Rottweiler. (Actually, there is no such breed as a Pit Bull — they’re usually a mix of an American Staffordshire Terrier and some other dog.) But even tenants of NYCHA have some recourse. For details, visit our Important Information for NYCHA Residents with Pets page.

According to the NYC Bar Association Committee on Legal Issues Pertaining to Animals, if your landlord refuses to make a reasonable accommodation after being notified of your rights, relief can be sought at the New York City Commission on Human Rights, at the NYS Division of Human Rights, and at the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity Enforcement, and in federal and state courts.

For a full description of your rights, contact an attorney knowledgeable in this area. You can find a lawyer through the NYC Bar’s Legal Referral Service at (212) 382-7373 or www.nycbar.org, or check our Legal Resources page.

On its website, the ASPCA advises, “If you are a NYCHA resident, you may have the legal right to keep your dog without risking your home. Contact attorney Darryl Vernon at (212) 949-7300 or dvernon@vgllp.com if you are approached by NYCHA management about your dog. Or you can contact the ASPCA Legal Department, 424 East 92nd Street, New York, NY 10128.

MFY Legal Services of New York City also publishes a comprehensive pamphlet on pet owners’ rights, Keeping Your Pet in a NYC Apartment: A Tenant’s Guide to New York City’s Pet Laws. Even before the introduction, it quotes Hon. Douglas E. McKeon in the case of 184 West 10th Street Corp. v. Marvits: “Indeed, so strong can be the bond between owner and pet that society recognizes the need for laws to protect each from the unscrupulous who would prey on one’s love for an animal to achieve their own selfish ends.”

Note: This article is not offered as legal advice and should not be relied upon for particular matters without the independent advice of counsel qualified in these issues. The law in this area changes frequently, and the information provide herein may be outdated. For counsel, contact your lawyer or one of the legal resources that can be found on our Legal Resources page.

by Jane Warshaw

Original post can be found here

Pets and Service Animals

For a condensed version of the information below, click here for a printable pdf.

More information on law changes is available here. Have your lease available when calling the Tenant Resource Center so we can help you know what your rights and remedies are, including whether you can sue your landlord for double damages, court costs and reasonable attorney fees.

Do I need permission to get a pet?

Probably! If you are currently in a lease, check your lease before you get a pet. If your lease requires permission to have a pet or to add a pet, make sure you get permission from your landlordin writing and keep a copy for your records. A landlord may just add something to your lease. Make sure both you and the landlord initial and date the change. If your landlord refuses to allow you to have a pet, wait until you move to a pet-friendly apartment. (From our blog: make sure toAssert the Rights You Have and Get It In Writing)

If you’re looking for a new apartment, make sure that you have permission in writing to have a pet.

What can happen if I get a pet without permission?

You could be evicted if it is prohibited in your lease. This would be a non-rent violation. The type of notice the landlord can give you, and whether you have a chance to get rid of the pet and avoid an eviction, will depend on several factors. For more information, please see Eviction. Being evicted makes it hard to find housing, can affect your credit, and does not relieve you from paying rent unless the landlord finds someone new to move in or your lease ends.

If one tenant has a pet, does the landlord have to allow everyone to have pets?

No. The landlord may give pet permission to some tenants and not others as long as they do notdiscriminate against certain tenants because of membership in a protected class, such as race, religion, sex, etc., or do it in retaliation against a tenant for enforcing their rights. It is not illegal for a landlord to discriminate against certain animals or breeds, as long as they are doing it for everyone.

What if I have a disability and depend on a service or companion animal?

This is a special situation. Because of federal fair housing laws that require landlords to allowreasonable accommodations for tenants with disabilities, the landlord may not prohibit a service animal or companion animal from living in the unit, or charge the tenant extra rent or security deposit. A service or companion animal should not be considered a pet. A service or companion animal should be treated, from the landlord’s perspective, like a piece of medical equipment.

While the Americans with Disabilities Act gives specific guidelines for what are and are not “service animals,” the Act says that “emotional support animals that do not qualify as service animals under the Department’s title III regulations may nevertheless qualify as permitted reasonable accommodations for persons with disabilities under the FHAct and the ACAA.” The Fair Housing Act, which addresses “reasonable accommodations” in rental housing, is available here.

The tenant may be required to provide a note from a physician that verifies the service or companion animal is needed as an accommodation to the person with the disability. Even though the animal does not need to be a certified service or companion animal and apartment applicants are not required to state anything about the animal on an application, tenants may be required to provide a letter upon request after they move in. This letter should be from a medical professional, and should include 2 important points:

- Tenant has a disability (the medical professional doesn’t need to state the kind of disability)

- That the animal is necessary to treat the disability that Tenant possesses (no certification or specification of what the animal does to treat the disability is necessary)

If the landlord refuses to allow the service or companion animal, you may contact:

How do I find landlords that rent to pet owners?

Check the regular rental listings–many landlords advertise that they allow pets. Some humane societies also keep lists of landlords who rent to people with pets. If you are looking for an apartment in Dane County, contact the Dane County Humane Society at (608) 838-0413, ext. 113. You can also search rental websites for units that allow pets.

How can I convince a landlord to rent to me and my pet?

Negotiate with the landlord

Contact the person who has the authority to grant you permission. This may be the resident manager, property manager, or owner of the building.

- Use some of our negotiation suggestions.

- Ask why the landlord has a no-pets policy. By asking up front about your landlord’s concerns, you can learn more about how to best present your own request. Considering your landlord’s position will encourage them to be more open to yours.

- When negotiating with the landlord, be careful about waiving a lot of rights in order to get permission for a pet. If the landlord seems unreasonable, you may want to keep looking for another apartment.

Market yourself as a good pet owner

Prepare a “pet resume” and include proof of your claims. Include the following in the resume:

- Good rental history. Write about your pet’s great rental history. Since some landlords require pet references, include letters of reference from current or previous landlords who can verify that your pet did not damage the apartments, and letters from neighbors who can attest to your pet’s good behavior and your own sense of responsibility.

- Training. Mention that your pet is well-behaved. If your cat is litter box trained or uses a scratching post, be sure to say so. If your dog does not bark when left alone or has attended obedience classes, mention this and include receipts or a graduation certificate.

- Veterinary records. State in the resume that your pets are well cared for and include copies of health certificates showing that your pets are spayed or neutered, free of fleas and ticks, and up-to-date on their vaccinations.

- Renters insurance. Depending on what kind of pet you have, you may be able to purchase liability insurance for any damage your pet may do. If you have this insurance, mention it in your resume and include a copy of your policy.

- Interview. Invite the landlord to “interview” your freshly groomed, well-behaved pet at your current home to show that your pet has not caused any damage.

Check out more detailed information and sample dog and cat resumes, or contact the Humane Society in your area.

In addition to presenting a pet resume, offer to sign a pet addendum to your rental agreement that makes you responsible for possible damage to property or injury to others.

Be a good pet owner

- If you have a dog, make sure to clean up its waste.

- Consider crate-training if you feel your dog may be destructive while you are not at home.

- Make sure your cat has access to a scratching post and that one or more litter boxes are readily available. If your cat is scratching something it shouldn’t be, try putting aluminum foil or double-stick tape in that area to deter the behavior.

- Talk to a veterinarian or other pet owners for advice on behavior issues.

Can landlords charge pet owners higher security deposits?

In the cities of Madison and Fitchburg, a security deposit cannot ever be more than one month’s rent.MGO 32.07(2)(b), FO 28.04(2)(a), Wis. Stat. 66.0104(2)(b)Eff. 12/21/11.

The State of Wisconsin imposes no limits on security deposit amounts. Landlords may charge pet owners more, but they must follow all the same laws about returning it. “Non-refundable” pet deposits are illegal. For more information on Security Deposits, see our pages for Security Deposits in Madison, and Security Deposits in Wisconsin.

Can landlords charge pet owners more for rent?

Yes, landlords may charge a monthly pet fee of whatever amount they choose. It is always worth trying to negotiate if you feel the extra amount is unreasonable. However, you should plan some extra time for this, and get everything in writing. See the section above on convincing landlords to rent to you and your pet for specific things you can mention to negotiate with your landlord.

Can landlords automatically withhold money from pet owners’ security deposits?

No, landlords may only charge for actual damages. If your pet did damage the apartment, the landlord may charge you for the repairs. If you are paying additional rent for your pet and being charged from your security deposit, make sure you’re not being double-charged. If your landlord charges for pet damages, you can ask them (or a judge) to credit you for the amount you’ve paid in pet fees. Ask to see receipts for charges a landlord claims. If you feel you are being charged unfairly, contact the Tenant Resource Center for more information, or see Security Deposits (Madison or Wisconsin).

Where can I get more information?

- The Humane Society of the United States has sample pet resumes and detailed information on how to find housing that accepts pets.

- The Dane County Humane Society has a list of landlords who rent to pet owners. (608) 838-0413

- Cats International provides information for cat owners.

The original post can be found here.

So, the clearest answer is probably “maybe.” When it was a flu-like illness confined to some regions in Africa, Zika wasn’t a high priority so research hasn’t been extensive. The risk to pets in areas where the virus is circulating (areas where there are Aedes egpyti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes) is probably very low. It would be good to look into the risks associated with domestic animals, including their susceptibility to disease and potential roles as reservoirs, but the likelihood that there is a relevant issue with either of these is probably remote.

So, the clearest answer is probably “maybe.” When it was a flu-like illness confined to some regions in Africa, Zika wasn’t a high priority so research hasn’t been extensive. The risk to pets in areas where the virus is circulating (areas where there are Aedes egpyti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes) is probably very low. It would be good to look into the risks associated with domestic animals, including their susceptibility to disease and potential roles as reservoirs, but the likelihood that there is a relevant issue with either of these is probably remote.